How to make your product spread to new networks (without changing what makes it great)

Ever notice something strange about project management software?

Jira dominates engineering but can't crack marketing teams. Notion captures creative agencies but struggles with traditional PMOs. Monday thrives with agencies but falters with dev teams. Basecamp endures with small teams while enterprise goes elsewhere.

In this post, you'll learn the hidden pattern behind successful product expansion - and how to use it to grow your market without compromising what makes your product special. Let's dive in.

Most people think this fragmentation is about features or market segments. But that's just what it looks like on the surface.

If it were about features, the best tools would eventually win their entire addressable market. If it were about segments, the most focused tools would own their niches completely.

But they don't. And there's a reason.

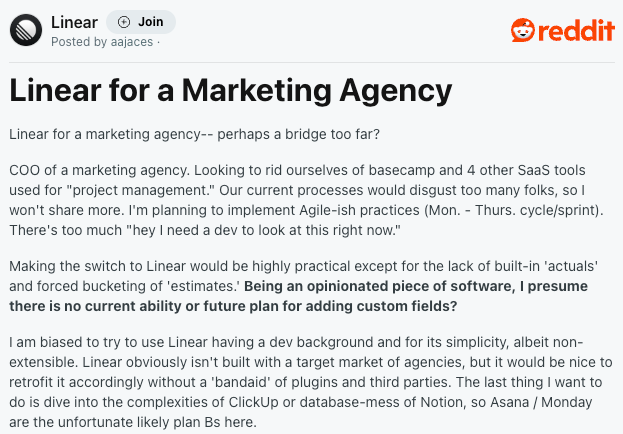

Let's look at a real example from a reddit thread: A marketing agency COO wrestling with a tool choice:

Despite using Basecamp and four other tools for project management, they're hesitant about adopting tools that lean too heavily into complexity like ClickUp or the "database-mess" of Notion.

Why?

Because TAM/SAM/SOM is missing the biggest market qualifier: worldview alignment.

And this is where most builders get it wrong.

The worldview puzzle

When you start looking for it, you see these worldview patterns everywhere. In every product category, in every market conversation, in every buying decision.

Here are three worldviews I spotted in that same thread:

The process pragmatist:

"Our current processes would disgust too many folks, so I won't share more."

They need tools that embrace messy reality. They know their processes aren't perfect, but they work.

The specialist skeptic:

"Linear is great for product teams - but is getting more niched w roadmaps, sprints"

They see specialization as a double-edged sword. In their world, tools that become too focused risk becoming irrelevant.

The flexibility first:

"Its a new product focused on teams working with agile with the flexibility to customize everything"

They see customization not as a feature but as a fundamental right.

Why this explains market fragmentation

Most product strategies stop at market segmentation. But once you understand worldviews, you start to see why even perfect segmentation fails. Here's what's really happening:

- Context clustering

Your real available market isn't:

- Companies in your sector (TAM)

- Companies who could buy (SAM)

- Companies you could reach (SOM)

It's:

- Networks who find themselves in similar contexts

- Who share similar worldviews

- At the same time

- Worldview lock-in

Once a tool aligns with a network's worldview, switching costs become psychological, not just technical. This is why:

- Jira users defend its complexity: "You need this structure for real engineering"

- Notion users evangelize its flexibility: "You can build anything you imagine"

- Monday users champion its adaptability: "It works the way your team works"

- The growth trap

Tools that try to expand beyond their worldview alignment often fail:

- Add flexibility for broader appeal → lose simplicity lovers

- Add structure for enterprise → lose startup adopters

- Add features for new segments → lose original advocates

But here's where it gets interesting. Some products do break through their natural ceiling. How?

The answer lies in a fascinating piece of marketing history from the 1920s that most people have never heard of.

Edward Bernays, Freud's nephew and the father of public relations, faced an interesting challenge.

The American Tobacco Company wanted to expand their market to women, but they faced a massive worldview barrier: smoking was considered taboo for women. The addressable market wasn't limited by features or demographics - it was limited by societal worldview.

Bernays' solution wasn't to change the product or target a different network. Instead, he orchestrated a worldview shift. During the 1929 Easter Sunday Parade in New York, he arranged for a group of young women to light up cigarettes in public, calling them "torches of freedom." He transformed cigarettes from a symbol of moral looseness into a symbol of female empowerment and liberation.

The result? The societal worldview shifted, and the addressable market exploded.

If you’re interested, watch this video to learn more about Bernay’s work.

Modern examples in action

While Bernays worked with cigarettes, today's category leaders are using the same psychological principles to transform how entire markets think about their work:

- Notion transcended "wiki tool" by becoming a symbol of "your team's second brain" - making knowledge management feel empowering rather than administrative. That's why you see people sharing their Notion setups like they're sharing productivity life hacks, not documentation systems.

- Airtable grew beyond "spreadsheet tool" by becoming a symbol of "anyone can build what they need" - transforming databases from IT territory into a tool for everyone. Now marketing teams build campaign trackers and event planners build conference schedules, without ever thinking "I'm using a database."

- Figma transcended "design tool" by becoming a symbol of "creativity without barriers" - transforming from a tool just for designers into the default whiteboard for any team collaboration. Now product managers run planning sessions and engineers sketch out architectures in Figma, without ever thinking "I'm using design software."

The shift in action

This isn't just theory. Once you know what to look for, you can see these worldview shifts happening in real-time:

Look at how Notion users talk about it - they don't say "I use Notion for documentation." They say "I run my life in Notion." That's not just product adoption. That's worldview transformation.

How companies could engineer worldview shifts

The real question isn't whether worldview shifts drive category leadership – it's how to engineer them deliberately. Here’s what I’d do:

Phase 1: Map your current worldview territory

Start by documenting the implicit beliefs of your current power users. Not just what they do with your product, but how they think about their work:

- What do they consider "real work" vs "busy work"?

- What do they take pride in?

- What do they apologize for?

- What do they brag about?

For example, early Figma users weren't just looking for design tools - they believed design should be collaborative, not siloed. That belief was key to Figma's expansion strategy.

Phase 2: Identify adjacent networks

Look for networks that share core beliefs with your current users, even if they work in different contexts. The key is finding philosophical alignment, not just feature-need fit.

Notion did this brilliantly:

- Core network: Tech teams who believed in building their own tools

- Adjacent network: Knowledge workers who wanted to design their own workspaces

- Shared belief: Systems should adapt to users, not vice versa

Phase 3: Create bridge stories

Develop narratives that help new networks see themselves in your product without alienating your core. This isn't about changing your product's features - it's about changing what your product symbolizes.

Consider Airtable's evolution:

- Original symbol: "Spreadsheets with superpowers"

- Bridge story: "Anyone can build what they need"

- New symbol: "Your ideas, your way"

The product didn't fundamentally change - the story about what it represents did.

Phase 4: Let your network lead

Your most powerful worldview shifters are often your existing users who already work across contexts. They naturally translate your value to new networks.

Notion's growth playbook:

- Tech teams used it for docs

- Those same people started using it for personal projects

- They became evangelists in their non-tech contexts

- New use cases emerged organically

The key is identifying and supporting these natural bridge-builders who already have influence across different networks.

Phase 5: Maintain worldview integrity

As you expand, resist the temptation to water down your core beliefs. Instead, show how those beliefs become even more valuable in new contexts.

Warning signs of worldview dilution:

- Marketing messages that contradict each other or sound too abstract

- Features that solve problems your product used to take a stance against

- User testimonials that showcase conflicting values

Remember: You're not trying to be everything to everyone. You're trying to show more networks that your worldview applies to their world too.

Measuring success:

Don't just track adoption metrics. Look for signs of worldview transformation:

- How do new networks describe your product to others?

- What adjacent problems do they start using it for?

- How do they defend it to skeptics?

The niche exception

Not every successful product needs to engineer worldview shifts. Some companies deliberately choose to deeply align with a specific worldview that's naturally expanding.

Linear and Basecamp exemplify this approach. While they compete in the project management space, they've chosen to deeply embed themselves in growing but distinct worldviews:

- Linear embraces the "engineering excellence" worldview: Where speed, keyboard shortcuts, and opinionated workflows aren't just features—they're symbols of craftsmanship. As more teams adopt engineering-led cultures, Linear grows without needing to shift worldviews.

- Basecamp champions the "less is more" worldview: Where simplicity and focus aren't compromises—they're competitive advantages. As more teams face tool fatigue and complexity overload, Basecamp's market expands naturally.

These companies prove that if your chosen worldview is growing fast enough, you might not need to engineer shifts. The key is ensuring your worldview alignment is deep enough to retain users as they grow, even if you never expand beyond that core belief system.

But while these niche players can build sustainable businesses by riding growing worldviews, the playbook for category leadership looks different. Category leaders don't just align with existing worldviews—they actively expand and transform them.

Your spread strategy checklist

To make your product spread to new networks:

- Map your current network's worldview (use the questions in Phase 1)

- Identify bridge-builders who already cross between networks

- Document how early adopters in new networks describe your product

- Craft stories that connect your core worldview to new contexts

- Support and amplify users who are already spreading your product naturally

Start with step 1 today: Interview three power users about how they think about their work (not just how they use your product).

The path forward

While most builders are still obsessing over feature parity and market fit, category leaders are quietly rewriting the rules of competition. They know something we don’t.

The next wave of category-defining products won't win by having better features or broader market reach. They'll win by understanding that growth isn't about expanding your addressable market - it's about expanding what your core worldview means to different networks.

Think about it:

- Jira didn't need to become less complex to win engineering teams

- Notion didn't need to become more structured to win creative teams

- Figma didn't need to become less design-focused to win collaboration

Instead, they showed different networks how their worldview solved problems in ways those networks hadn't imagined.

Your product's growth ceiling isn't set by your features, your market size, or even your execution. It's set by how successfully you can transform your worldview from a tool perspective ("this is project management software") into a movement perspective ("this is how modern teams should work").

Because in the end, there are no total addressable markets. Only expandable worldviews. And the products that win aren't just the ones with the best solutions - they're the ones that change how networks think about the problem itself.

Much of the thinking in this piece was inspired by Diego de Jódar's excellent work at pleasedontpush.com. His insights on startup growth strategy have been instrumental in shaping these ideas.